Illuminati

光照派

The Illuminati[1] (plural of Latin illuminatus, 'enlightened') is a name given to several groups, both real and fictitious. Historically, the name usually refers to the Bavarian Illuminati, an Enlightenment-era secret society founded on 1 May 1776 in Bavaria, today part of Germany. The society's goals were to oppose superstition, obscurantism, religious influence over public life, and abuses of state power. "The order of the day," they wrote in their general statutes, "is to put an end to the machinations of the purveyors of injustice, to control them without dominating them."[2] The Illuminati—along with Freemasonry and other secret societies—were outlawed through edict by Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria, with the encouragement of the Catholic Church, in 1784, 1785, 1787, and 1790.[3] During subsequent years, the group was generally vilified by conservative and religious critics who claimed that the Illuminati continued underground and were responsible for the French Revolution.

光照派[1](拉丁文 illuminatus 的复数,‘顿悟’)是一个名字,给几个团体,包括真实的和虚构的。历史上,这个名字通常指的是光照派,一个启蒙运动时期的秘密组织,成立于1776年5月1日,位于巴伐利亚,今天是德国的一部分。这个社会的目标是反对迷信、蒙昧主义、宗教对公共生活的影响和滥用国家权力。“今天的秩序,”他们在他们的总章程中写道,“就是结束不公正的提供者的阴谋诡计,控制他们而不支配他们。”[2]1784年、1785年、1787年和1790年,在天主教会的鼓励下,巴伐利亚选帝侯查尔斯 · 西奥多颁布法令,禁止了光明会和共济会及其他秘密社团的活动。[3]在随后的几年里,这个组织受到保守派和宗教批评家的普遍诋毁,他们声称光照派继续秘密活动,并对法国大革命负有责任。

Many influential intellectuals and progressive politicians counted themselves as members, including Ferdinand of Brunswick and the diplomat Franz Xaver von Zach, who was the Order's second-in-command.[4] It attracted literary men such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottfried Herder, and the reigning Duke of Gotha and of Weimar.[5]

许多有影响力的知识分子和进步派政治家都将自己视为圣殿成员,其中包括布伦瑞克的费迪南德和外交官、圣殿二号人物弗朗茨 · 谢维尔 · 冯 · 扎克(Franz Xaver von Zach)。它吸引了一些文学家,比如约翰·沃尔夫冈·冯·歌德和约翰·哥特弗雷德·赫尔德,还有哥达和魏玛的公爵。[5]

In subsequent use, "Illuminati" has referred to various organisations which have claimed, or have been claimed to be, connected to the original Bavarian Illuminati or similar secret societies, though these links have been unsubstantiated. These organisations have often been alleged to conspire to control world affairs, by masterminding events and planting agents in government and corporations, in order to gain political power and influence and to establish a New World Order. Central to some of the more widely known and elaborate conspiracy theories, the Illuminati have been depicted as lurking in the shadows and pulling the strings and levers of power in dozens of novels, films, television shows, comics, video games, and music videos.

在随后的使用中,“光照派”指的是各种各样的组织,这些组织声称或已经声称与最初的光照派或类似的秘密社团有联系,尽管这些联系没有得到证实。这些组织经常被指控密谋控制世界事务,策划事件,在政府和企业中安插代理人,以获得政治权力和影响力,并建立新的世界秩序。在一些更广为人知、更精心策划的阴谋理论中,光照派被描绘成潜伏在阴影中,在数十部小说、电影、电视节目、漫画、视频游戏和音乐视频中操纵着弦线和权力杠杆。

History 历史

Origins 起源

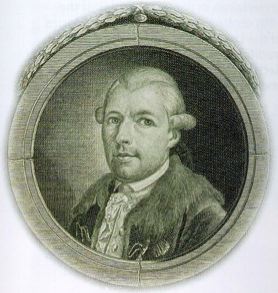

Adam Weishaupt (1748–1830) became professor of Canon Law and practical philosophy at the University of Ingolstadt in 1773. He was the only non-clerical professor at an institution run by Jesuits, whose order Pope Clement XIV had dissolved in 1773. The Jesuits of Ingolstadt, however, still retained the purse strings and some power at the university, which they continued to regard as their own. They made constant attempts to frustrate and discredit non-clerical staff, especially when course material contained anything they regarded as liberal or Protestant. Weishaupt became deeply anti-clerical, resolving to spread the ideals of the Enlightenment (Aufklärung) through some sort of secret society of like-minded individuals.[6]

亚当 · 威斯豪普特(1748-1830)于1773年成为英戈尔斯塔特大学教会法和实践哲学教授。他是耶稣会士管理的机构中唯一的非教士教授,该克雷芒十四世于1773年解散。然而,英戈尔斯塔特的耶稣会士仍然掌控着大学的财政和一些权力,他们继续视之为自己的权力。他们不断试图挫败和诋毁非办事人员,特别是当课程材料中包含他们认为是自由主义者或新教徒的任何东西时。威斯豪普特变得非常反教会,决心通过一些志同道合的个人组成的秘密社团来传播启蒙运动的理想。[6]

Finding Freemasonry expensive, and not open to his ideas, he founded his own society which was to have a system of ranks or grades based on those in Freemasonry, but with his own agenda.[6] His original name for the new order was Bund der Perfektibilisten, or Covenant of Perfectibility (Perfectibilists); he later changed it because it sounded too strange.[7] On 1 May 1776, Weishaupt and four students formed the Perfectibilists, taking the Owl of Minerva as their symbol.[8][9] The members were to use aliases within the society. Weishaupt became Spartacus. Law students Massenhausen, Bauhof, Merz and Sutor became respectively Ajax, Agathon, Tiberius and Erasmus Roterodamus. Weishaupt later expelled Sutor for indolence.[10][11] In April 1778, the order became the Illuminatenorden, or Order of Illuminati, after Weishaupt had seriously contemplated the name Bee order.[12]

他发现共济会费用昂贵,而且不接受他的思想,于是他建立了自己的社团,这个社团有一套基于共济会成员的等级和等级制度,但是有自己的议程。[6]他最初给这个新秩序起的名字是“完美主义者联盟”(bunder Perfektibilisten) ,后来又改成了“完美主义者联盟”,因为听起来太奇怪了。1776年5月1日,魏思豪普特和四个学生组成了完美主义者,他们把密涅瓦的猫头鹰作为他们的象征。成员们在社团内使用别名。威斯豪普特变成了斯巴达克斯。法学院学生马森豪森、鲍霍夫、默兹和苏特分别成为阿贾克斯、阿加森、提比略和伊拉斯莫斯 · 罗特罗达马斯。后来,韦斯豪普特以懒惰为由开除了萨托尔。[10][11]1778年4月,在威斯豪普特认真考虑了蜜蜂的命名后,这个组织成为了光照派的组织。[12]

Massenhausen proved initially the most active in expanding the society. Significantly, while studying in Munich shortly after the formation of the order, he recruited Xavier von Zwack, a former pupil of Weishaupt at the beginning of a significant administrative career. (At the time, he was in charge of the Bavarian National Lottery.) Massenhausen's enthusiasm soon became a liability in the eyes of Weishaupt, often resulting in attempts to recruit unsuitable candidates. Later, his erratic love-life made him neglectful, and as Weishaupt passed control of the Munich group to Zwack, it became clear that Massenhausen had misappropriated subscriptions and intercepted correspondence between Weishaupt and Zwack. In 1778, Massenhausen graduated and took a post outside Bavaria, taking no further interest in the order. At this time, the order had a nominal membership of twelve.[10]

事实最初证明,马森豪森在扩大社会方面最为活跃。值得注意的是,在该组织成立后不久,他就在慕尼黑学习,并招募了泽维尔 · 冯 · 兹瓦克,这位维索普特的前学生在他重要的行政职业生涯的开始。(当时,他负责巴伐利亚国家彩票。)马森豪森的热情很快成为 Weishaupt 眼中的负担,经常导致有人试图招募不合适的候选人。后来,他飘忽不定的爱情生活使他疏忽大意,当威斯豪普特把慕尼黑集团的控制权交给兹瓦克时,很明显,马森豪森盗用了威斯豪普特和兹瓦克之间的订阅和通信。1778年,马森豪森毕业后在巴伐利亚州外谋得一个职位,没有再对这个勋章感兴趣。在这个时候,该命令有十二名名义会员。[10]

With the departure of Massenhausen, Zwack immediately applied himself to recruiting more mature and important recruits. Most prized by Weishaupt was Hertel, a childhood friend and a canon of the Munich Frauenkirche. By the end of summer 1778 the order had 27 members (still counting Massenhausen) in 5 commands; Munich (Athens), Ingolstadt (Eleusis), Ravensberg (Sparta), Freysingen (Thebes), and Eichstaedt (Erzurum).[10]

随着马森豪森的离开,扎克立即着手招募更成熟、更重要的新人。其中最有价值的是赫特尔,他是威斯豪普特儿时的朋友,也是圣母教堂的教士。到1778年夏末为止,该修道会已有27名成员(仍包括马森豪森) ,分属5个指挥部: 慕尼黑(雅典)、英戈尔斯塔特(爱露西斯)、拉文斯堡(斯巴达)、弗雷辛根(底比斯)和艾克斯塔特(埃尔祖鲁姆)。[10]

During this early period, the order had three grades of Novice, Minerval, and Illuminated Minerval, of which only the Minerval grade involved a complicated ceremony. In this the candidate was given secret signs and a password. A system of mutual espionage kept Weishaupt informed of the activities and character of all his members, his favourites becoming members of the ruling council, or Areopagus. Some novices were permitted to recruit, becoming Insinuants. Christians of good character were actively sought, with Jews and pagans specifically excluded, along with women, monks, and members of other secret societies. Favoured candidates were rich, docile, willing to learn, and aged 18–30.[13][14]

在早期阶段,这个秩序有三个等级: 新手,Minerval 和照亮密涅瓦,其中只有密涅瓦级涉及一个复杂的仪式。在这个过程中,候选人被给予了暗号和密码。一个相互间谍的系统不断告知魏斯豪普特他所有成员的活动和性格,他最喜欢的成员成为执政委员会的成员,或称为阿鲁巴古斯。一些新手被允许招募,成为影射者。具有良好品格的基督徒被积极地寻找,犹太人和异教徒被明确地排除在外,还有妇女、僧侣和其他秘密社团的成员。受到青睐的候选人富有、温顺、愿意学习,年龄在18-30岁之间。[14]

Transition 过渡期

Having, with difficulty, dissuaded some of his members from joining the Freemasons, Weishaupt decided to join the older order to acquire material to expand his own ritual. He was admitted to lodge "Prudence" of the Rite of Strict Observance early in February 1777. His progress through the three degrees of "blue lodge" masonry taught him nothing of the higher degrees he sought to exploit, but in the following year a priest called Abbé Marotti informed Zwack that these inner secrets rested on knowledge of the older religion and the primitive church. Zwack persuaded Weishaupt that their own order should enter into friendly relations with Freemasonry, and obtain the dispensation to set up their own lodge. At this stage (December 1778), the addition of the first three degrees of Freemasonry was seen as a secondary project.[15]

经过艰难的劝阻,他的一些成员不要加入共济会,魏斯豪普特决定加入旧秩序,以获取材料来扩展他自己的仪式。1777年2月初,他被允许入住严密仪式的普鲁登斯旅馆。他在三个不同程度的”蓝屋”砖石建筑中取得的进步并没有教会他想要开发的更高程度的东西,但是第二年,一位名叫 Abbé Marotti 的牧师告诉 Zwack,这些内在的秘密建立在对古老宗教和原始教会的了解之上。兹瓦克说服威斯豪普特,他们自己的修会应该与共济会建立友好关系,并获得特许建立自己的分会。在这个阶段(1778年12月) ,共济会前三个等级的增加被视为一个次要项目。[15]

With little difficulty, a warrant was obtained from the Grand Lodge of Prussia called the Royal York for Friendship, and the new lodge was called Theodore of the Good Council, with the intention of flattering Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria. It was founded in Munich on 21 March 1779, and quickly packed with Illuminati. The first master, a man called Radl, was persuaded to return home to Baden, and by July Weishaupt's order ran the lodge.[15]

不费吹灰之力,从普鲁士的皇家约克友谊大会堂拿到了许可证,这个新会所叫做善会的西奥多,意在奉承巴伐利亚选帝侯查尔斯 · 西奥多。它于1779年3月21日在慕尼黑成立,并迅速与光明会合作。第一个主人,一个叫拉德尔的人,被说服回到巴登的家中,到了七月,威斯豪普特的命令传遍了整个小屋。[15]

The next step involved independence from their Grand Lodge. By establishing masonic relations with the Union lodge in Frankfurt, affiliated to the Premier Grand Lodge of England, lodge Theodore became independently recognised, and able to declare its independence. As a new mother lodge, it could now spawn lodges of its own. The recruiting drive amongst the Frankfurt masons also obtained the allegiance of Adolph Freiherr Knigge.[15]

下一步是从他们的大旅馆中独立出来。通过与附属于英格兰总理大会的法兰克福联合会建立共济会关系,西奥多得到了独立的承认,并能够宣布其独立。作为一个新的母亲住所,它现在可以产生自己的小屋。法兰克福共济会中的招募活动也得到了阿道夫 · 弗赖赫尔 · 克尼格的拥护。[15]

Reform 改革

Adolph Knigge 阿道夫 · 克尼格

Knigge was recruited late in 1780 at a convention of the Rite of Strict Observance by Costanzo Marchese di Costanzo, an infantry captain in the Bavarian army and a fellow Freemason. Knigge, still in his twenties, had already reached the highest initiatory grades of his order, and had arrived with his own grand plans for its reform. Disappointed that his scheme found no support, Knigge was immediately intrigued when Costanzo informed him that the order that he sought to create already existed. Knigge and three of his friends expressed a strong interest in learning more of this order, and Costanzo showed them material relating to the Minerval grade. The teaching material for the grade was "liberal" literature which was banned in Bavaria, but common knowledge in the Protestant German states. Knigge's three companions became disillusioned and had no more to do with Costanzo, but Knigge's persistence was rewarded in November 1780 by a letter from Weishaupt. Knigge's connections, both within and outside of Freemasonry, made him an ideal recruit. Knigge, for his own part, was flattered by the attention, and drawn towards the order's stated aims of education and the protection of mankind from despotism. Weishaupt managed to acknowledge, and pledge to support, Knigge's interest in alchemy and the "higher sciences". Knigge replied to Weishaupt outlining his plans for the reform of Freemasonry as the Strict Observance began to question its own origins.[16]

1780年晚些时候,Knigge 在严密仪式的一次会议上被 Costanzo Marchese di Costanzo 招募,Costanzo 是巴伐利亚军队的一名步兵上尉,也是共济会员。当时康吉还是二十多岁,已经达到了他的修会的最高级别,并且带着他自己的宏伟计划来到了这里。康尼格对自己的计划没有得到支持感到失望,当康斯坦佐告诉他,他想要创建的订单已经存在时,他立刻产生了兴趣。康吉和他的三个朋友表示有兴趣进一步了解这个顺序,科斯坦佐向他们展示了与密涅瓦级别有关的材料。这个年级的教材是“自由”文学,这在巴伐利亚是被禁止的,但在德国新教州却是常识。康尼奇的三个同伴对科斯坦佐的死不再抱有幻想,但康尼奇的坚持在1780年11月收到了威斯豪普特的一封信。康吉在共济会内外的关系使他成为一个理想的新成员。克尼格本人对这种关注感到高兴,并被吸引到教育和保护人类免受专制统治的既定目标中去。维斯豪普特承认并保证支持康尼奇对炼金术和“更高科学”的兴趣。康吉对威斯豪普特的回答概述了他对共济会进行改革的计划,因为严格遵守计划开始质疑它自己的起源。[16]

Weishaupt set Knigge the task of recruiting before he could be admitted to the higher grades of the order. Knigge accepted, on the condition that he be allowed to choose his own recruiting grounds. Many other masons found Knigge's description of the new masonic order attractive, and were enrolled in the Minerval grade of the Illuminati. Knigge appeared at this time to believe in the "Most Serene Superiors" which Weishaupt claimed to serve. His inability to articulate anything about the higher degrees of the order became increasingly embarrassing, but in delaying any help, Weishaupt gave him an extra task. Provided with material by Weishaupt, Knigge now produced pamphlets outlining the activities of the outlawed Jesuits, purporting to show how they continued to thrive and recruit, especially in Bavaria. Meanwhile, Knigge's inability to give his recruits any satisfactory response to questions regarding the higher grades was making his position untenable, and he wrote to Weishaupt to this effect. In January 1781, faced with the prospect of losing Knigge and his masonic recruits, Weishaupt finally confessed that his superiors and the supposed antiquity of the order were fictions, and the higher degrees had yet to be written.[16]

威斯豪普特在康尼格能够进入更高等级的教会之前,就派他去招募人员。克尼格接受了,条件是允许他选择自己的招募地点。许多其他共济会成员认为克尼格对共济会新秩序的描述很有吸引力,因此加入了光照派的密涅瓦级别。这时候,康尼奇似乎相信魏思豪普特所说的“最高贵的长者”。他不能清楚地表达出更高等级的秩序变得越来越令人尴尬,但是为了拖延任何帮助,威斯豪普特给了他一个额外的任务。在魏思豪普特提供的材料的帮助下,康尼格现在制作了宣传小册子,概述了被取缔的耶稣会士的活动,号称展示了他们如何继续发展和招募,特别是在巴伐利亚。同时,Knigge 无法给他的新兵任何令人满意的答复,有关更高的等级的问题,使他的立场难以为继,他写信给魏绍普特,大意是这样的。1781年1月,面对着失去康尼格和他的共济会新兵的前景,威斯豪普特终于承认,他的上级和所谓的古老秩序都是虚构的,更高的学位还没有写出来。[16]

If Knigge had expected to learn the promised deep secrets of Freemasonry in the higher degrees of the Illuminati, he was surprisingly calm about Weishaupt's revelation. Weishaupt promised Knigge a free hand in the creation of the higher degrees, and also promised to send him his own notes. For his own part, Knigge welcomed the opportunity to use the order as a vehicle for his own ideas. His new approach would, he claimed, make the Illuminati more attractive to prospective members in the Protestant kingdoms of Germany. In November 1781 the Areopagus advanced Knigge 50 florins to travel to Bavaria, which he did via Swabia and Franconia, meeting and enjoying the hospitality of other Illuminati on his journey.[17]

如果康尼格希望了解共济会在光明会更高阶层中承诺的深层秘密,他对威斯豪普特的启示惊人地冷静。魏思豪普特答应让康尼奇自由地创造高等学位,并答应给他寄去他自己的笔记。对于他自己来说,Knigge 很高兴有机会利用这个订单来实现他自己的想法。他声称,他的新方法将使光照派对德国新教王国的潜在成员更具吸引力。1781年11月,阿雷奥帕古斯预付了克尼格50弗罗林前往巴伐利亚,途经 Swabia 和弗朗科尼亚,与其他光照派成员会面并享受他旅途中的热情款待。[17]

Internal problems 内部问题

The order had now developed profound internal divisions. The Eichstaedt command had formed an autonomous province in July 1780, and a rift was growing between Weishaupt and the Areopagus, who found him stubborn, dictatorial, and inconsistent. Knigge fitted readily into the role of peacemaker.[17]

这一命令现在已经发展成为深刻的内部分歧。艾希施泰特指挥部在1780年7月成立了一个自治省,威斯豪普特和阿雷奥帕古斯之间的裂痕正在扩大,阿雷奥帕古斯发现他顽固、独裁、反复无常。克尼格很适合做和事佬的角色。[17]

In discussions with the Areopagus and Weishaupt, Knigge identified two areas which were problematic. Weishaupt's emphasis on the recruitment of university students meant that senior positions in the order often had to be filled by young men with little practical experience. Secondly, the anti-Jesuit ethos of the order at its inception had become a general anti-religious sentiment, which Knigge knew would be a problem in recruiting the senior Freemasons that the order now sought to attract. Knigge felt keenly the stifling grip of conservative Catholicism in Bavaria, and understood the anti-religious feelings that this produced in the liberal Illuminati, but he also saw the negative impression these same feelings would engender in Protestant states, inhibiting the spread of the order in greater Germany. Both the Areopagus and Weishaupt felt powerless to do anything less than give Knigge a free hand. He had the contacts within and outside of Freemasonry that they needed, and he had the skill as a ritualist to build their projected gradal structure, where they had ground to a halt at Illuminatus Minor, with only the Minerval grade below and the merest sketches of higher grades. The only restrictions imposed were the need to discuss the inner secrets of the highest grades, and the necessity of submitting his new grades for approval.[17]

在与 Areopagus 和 Weishaupt 的讨论中,Knigge 确定了两个存在问题的领域。魏绍普特强调招收大学生,这意味着高级职位往往不得不由几乎没有实际经验的年轻人担任。其次,该教团成立之初的反耶稣会风气已经成为一种普遍的反宗教情绪,克尼格知道,这种情绪会对招募高级共济会成员造成困难,而该教团现在正试图吸引这些高级共济会成员。克尼格敏锐地感受到保守的天主教在巴伐利亚令人窒息的控制,理解自由的光照派由此产生的反宗教情绪,但他也看到这些情绪会在新教国家产生的负面印象,抑制了秩序在大德国的传播。除了让康尼基自由行动,阿鲁帕格斯号和威斯豪普特号都感到无能为力。他在共济会内外都有他们需要的联系人,作为一个仪式主义者,他有能力建立他们的计划梯级结构,在那里他们在光明小教会停滞不前,只有密涅瓦级别低于和更高级别的草图。唯一的限制是需要讨论最高级别的内部秘密,以及必须提交他的新成绩审批。[17]

Meanwhile, the scheme to propagate Illuminatism as a legitimate branch of Freemasonry had stalled. While Lodge Theodore was now in their control, a chapter of "Elect Masters" attached to it only had one member from the order, and still had a constitutional superiority to the craft lodge controlled by the Illuminati. The chapter would be difficult to persuade to submit to the Areopagus, and formed a very real barrier to Lodge Theodore becoming the first mother-lodge of a new Illuminated Freemasonry. A treaty of alliance was signed between the order and the chapter, and by the end of January 1781 four daughter lodges had been created, but independence was not in the chapter's agenda.[17]

与此同时,宣传光明主义作为共济会合法分支的计划已经停止。虽然洛奇西奥多现在是在他们的控制,一个章节的“选举大师”附加到它只有一个成员从秩序,并仍然有一个宪法优势的工艺小屋控制由光照派。这个章节将很难说服服从阿略帕戈斯,并形成了一个非常真正的障碍洛奇西奥多成为第一个母亲分会的新的照明共济会。修道院和修道院之间签订了联盟条约,到1781年1月底,修道院建立了四个女儿旅馆,但是独立不在修道院的议事日程上。[17]

Costanza wrote to the Royal York pointing out the discrepancy between the fees dispatched to their new Grand Lodge and the service they had received in return. The Royal York, unwilling to lose the revenue, offered to confer the "higher" secrets of Freemasonry on a representative that their Munich brethren would dispatch to Berlin. Costanza accordingly set off for Prussia on 4 April 1780, with instructions to negotiate a reduction in Theodore's fees while he was there. On the way, he managed to have an argument with a Frenchman on the subject of a lady with whom they were sharing a carriage. The Frenchman sent a message ahead to the king, some time before they reached Berlin, denouncing Costanza as a spy. He was only freed from prison with the help of the Grand Master of Royal York, and was expelled from Prussia having accomplished nothing.[17]

科斯坦萨写信给皇家约克报,指出寄给他们新的格兰德洛奇旅馆的费用与他们得到的回报之间的差异。不愿失去收入的约克皇家学会(Royal York)提出,将共济会的“更高”机密授予其慕尼黑同胞派往柏林的代表。于是,科斯坦萨于1780年4月4日动身前往普鲁士,奉命在西奥多在那里期间谈判减少他的费用。在路上,他设法和一个法国人就他们同乘一辆马车的一位女士发生了争执。在抵达柏林之前,法国人事先给国王发了一条信息,谴责科斯坦萨是间谍。他只是在皇家约克大师的帮助下才从监狱中释放出来,并且在没有完成任何事情的情况下被普鲁士驱逐出境。[17]

New system 新系统

Knigge's initial plan to obtain a constitution from London would, they realised, have been seen through by the chapter. Until such time as they could take over other masonic lodges that their chapter could not control, they were for the moment content to rewrite the three degrees for the lodges which they administered.[17]

他们意识到,克尼格最初从伦敦获得宪法的计划将被该章看穿。直到他们能够接管其他共济会所,他们的章节无法控制的时候,他们暂时满足于为他们管理的共济会所改写三个度。[17]

On 20 January 1782, Knigge tabulated his new system of grades for the order. These were arranged in three classes:

1782年1月20日,Knigge 将他的新等级制成表格,这些等级分为三类:

- Class I – The nursery, consisting of the Noviciate, the Minerval, and Illuminatus minor.

- 一级-托儿所,包括初学者,Minerval,和光照派小学。

- Class II – The Masonic grades. The three "blue lodge" grades of Apprentice, Companion, and Master were separated from the higher "Scottish" grades of Scottish Novice and Scottish Knight.

- 第二班-共济会成绩。学徒、伴侣和大师的三个“蓝色小屋”等级与苏格兰新手和苏格兰骑士的高等“苏格兰”等级分开。

- Class III – The Mysteries. The lesser mysteries were the grades of Priest and Prince, followed by the greater mysteries in the grades of Mage and King. It is unlikely that the rituals for the greater mysteries were ever written.[17][18]

- 第三类-奥秘。较小的谜团是牧师和王子的等级,其次是 Mage 和国王的等级更大的谜团。更大的神秘事件的仪式不太可能被记录下来。[18]

Attempts at expansion 扩张的尝试

Knigge's recruitment from German Freemasonry was far from random. He targeted the masters and wardens, the men who ran the lodges, and were often able to place the entire lodge at the disposal of the Illuminati. In Aachen, Baron de Witte, master of Constancy lodge, caused every member to join the order. In this way, the order expanded rapidly in central and southern Germany, and obtained a foothold in Austria. Moving into the Spring of 1782, the handful of students that had started the order had swelled to about 300 members, only 20 of the new recruits being students.[19]

康尼格从德国共济会中招募的人员绝非随机的。他的目标是主人和看守,那些经营小屋的人,并且经常能够将整个小屋置于光照派的支配之下。在亚琛,康斯坦西小屋的主人德维特男爵号召所有成员加入教会。这样,秩序在德国中部和南部迅速扩张,并在奥地利获得了立足点。到了1782年春天,开始这个项目的少数学生已经增加到大约300人,其中只有20人是学生。[19]

In Munich, the first half of 1782 saw huge changes in the government of Lodge Theodore. In February, Weishaupt had offered to split the lodge, with the Illuminati going their own way and the chapter taking any remaining traditionalists into their own continuation of Theodore. At this point, the chapter unexpectedly capitulated, and the Illuminati had complete control of lodge and chapter. In June, both lodge and chapter sent letters severing relations with Royal York, citing their own faithfulness in paying for their recognition, and Royal York's failure to provide any instruction into the higher grades. Their neglect of Costanza, failure to defend him from malicious charges or prevent his expulsion from Prussia, were also cited. They had made no effort to provide Costanza with the promised secrets, and the Munich masons now suspected that their brethren in Berlin relied on the mystical French higher grades which they sought to avoid. Lodge Theodore was now independent.[19]

在慕尼黑,1782年上半年见证了洛奇 · 西奥多政府的巨大变化。今年二月,威斯豪普特提出分开这个小屋,光照派走他们自己的路,而这一章则把所有剩下的传统主义者带入他们自己的西奥多的延续。在这一点上,章意外地投降,和光照派完全控制分会和章。今年6月,分会和分会都发出信件,断绝与皇家约克公司的关系,理由是他们自己在为他们的认可支付费用方面的忠诚,以及皇家约克公司未能提供任何关于更高等级的指导。他们对科斯坦萨的忽视,未能为他的恶意指控进行辩护,也未能阻止他被普鲁士驱逐出境。他们没有努力向科斯坦萨提供所承诺的秘密,慕尼黑的共济会会员现在怀疑他们在柏林的兄弟依赖于他们试图避免的神秘的法国高分。洛奇 · 西奥多现在独立了。[19]

The Rite of Strict Observance was now in a critical state. Its nominal leader was Prince Carl of Södermanland (later Charles XIII of Sweden), openly suspected of trying to absorb the rite into the Swedish Rite, which he already controlled. The German lodges looked for leadership to Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Suspicion turned to open contempt when it transpired that Carl regarded the Stuart heir to the British throne as the true Grand Master, and the lodges of the Strict Observance all but ignored their Grand Master. This impasse led to the Convent of Wilhelmsbad.[19]

严密仪式现在处于危急状态。其名义上的领导人是 Södermanland 王子卡尔(后来的卡尔十三世) ,公开怀疑他试图将这种仪式纳入他已经控制的瑞典仪式。德国人开始寻找斐迪南的领导者。当卡尔发现斯图尔特家族的英国王位继承人是真正的大师时,怀疑变成了公开的蔑视,严格遵守协议的分会几乎对他们的大师视而不见。这种僵局导致了 Wilhelmsbad 修道院。[19]

Convent of Wilhelmsbad 威廉斯巴德修道院

Delayed from 15 October 1781, the last convention of the Strict Observance finally opened on 16 July 1782 in the spa town of Wilhelmsbad on the outskirts of (now part of) Hanau. Ostensibly a discussion of the future of the order, the 35 delegates knew that the Strict Observance in its current form was doomed, and that the Convent of Wilhelmsbad would be a struggle over the pieces between the German mystics, under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and their host Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, and the Martinists, under Jean-Baptiste Willermoz. The only dissenting voices to mystical higher grades were Johann Joachim Christoph Bode, who was horrified by Martinism, but whose proposed alternatives were as yet unformed, and Franz Dietrich von Ditfurth, a judge from Wetzlar and master of the Joseph of the Three Helmets lodge there, who was already a member of the Illuminati. Ditfurth publicly campaigned for a return to the basic three degrees of Freemasonry, which was the least likely outcome of the convention. The mystics already had coherent plans to replace the higher degrees.[19]

1781年10月15日被推迟的最后一次严格遵守纪律大会终于于1782年7月16日在哈瑙(现为)郊区的温泉小镇 Wilhelmsbad 开幕。表面上是讨论教会的未来,35名代表知道目前这种严格的仪式注定要失败,而且威廉斯巴德修道院将会是德国神秘主义者在斐迪南和他们的东道主查尔斯伯爵(黑森-卡塞尔) ,以及尚-巴蒂斯特·惠勒莫领导下的马丁主义者之间的斗争。只有约翰 · 约阿希姆 · 克里斯托夫 · 波德和弗朗茨 · 迪特里希 · 冯 · 迪特弗斯,一位来自韦茨拉尔的法官,也是那里三头盔约瑟夫分会的主席,他们已经是光照派的成员。迪特福斯公开竞选,要求回归共济会的基本三个等级,这是共济会最不可能的结果。神秘主义者已经有了一个连贯的计划来取代更高的学位。[19]

The lack of a coherent alternative to the two strains of mysticism allowed the Illuminati to present themselves as a credible option. Ditfurth, prompted and assisted by Knigge, who now had full authority to act for the order, became their spokesman. Knigge's original plan to propose an alliance between the two orders was rejected by Weishaupt, who saw no point in an alliance with a dying order. His new plan was to recruit the masons opposed to the "Templar" higher degree of the Strict Observance.[19]

缺乏一个连贯的替代的两种神秘主义允许光照派自己呈现作为一个可信的选择。迪特福斯在康尼格的提示和协助下,成为了他们的发言人,康尼格现在完全有权代表这项命令行事。康尼基最初提出的两个订单结盟的计划遭到了威斯豪普特的拒绝,他认为与一个垂死的订单结盟毫无意义。他的新计划是招募反对严格遵守更高级别的“圣殿骑士”的共济会会员。[19]

At the convent, Ditfurth blocked the attempts of Willermoz and Hesse to introduce their own higher grades by insisting that full details of such degrees be revealed to the delegates. The frustration of the German mystics led to their enrolling Count Kollowrat with the Illuminati with a view to later affiliation. Ditfurth's own agenda was to replace all of the higher degrees with a single fourth degree, with no pretensions to further masonic revelations. Finding no support for his plan, he left the convent prematurely, writing to the Areopagus that he expected nothing good of the assembly.[19]

在修道院,迪特福坚持要求向代表们透露学位的全部细节,从而阻止了 Willermoz 和黑森提高学位等级的努力。德国神秘主义者的挫败感导致他们将柯洛瑞特伯爵纳入光明会,以期日后加入光明会。迪特福特自己的议程是用一个单一的第四级取代所有高级学位,没有自命进一步共济会的启示。他的计划没有得到任何支持,于是过早地离开了修道院,给阿略巴古斯写信说,他对会众没有任何好感。[19]

In an attempt to satisfy everybody, the Convent of Wilhelmsbad achieved little. They renounced the Templar origins of their ritual, while retaining the Templar titles, trappings and administrative structure. Charles of Hesse and Ferdinand of Brunswick remained at the head of the order, but in practice the lodges were almost independent. The Germans also adopted the name of the French order of Willermoz, les Chevaliers bienfaisants de la Cité sainte (Good Knights of the Holy City), and some Martinist mysticism was imported into the first three degrees, which were now the only essential degrees of Freemasonry. Crucially, individual lodges of the order were now allowed to fraternise with lodges of other systems. The new "Scottish Grade" introduced with the Lyon ritual of Willermoz was not compulsory, each province and prefecture was free to decide what, if anything, happened after the three craft degrees. Finally, in an effort to show that something had been achieved, the convent regulated at length on etiquette, titles, and a new numbering for the provinces.[19]

为了使大家都满意,威廉斯巴德修院收效甚微。他们放弃了圣殿骑士的起源,同时保留了圣殿骑士的头衔、服饰和行政结构。黑森的查尔斯和布伦瑞克的费迪南仍然是教会的领袖,但实际上,这些分会几乎是独立的。德国人还采用了法国的 Willermoz 骑士团的名字,圣城的好骑士,一些马丁主义的神秘主义被输入到前三个等级,这是现在共济会唯一的基本等级。至关重要的是,现在已经允许这一阶层的个人分会与其他系统的分会交往。在里昂的威勒莫兹仪式中引入的新的“苏格兰等级”并不是强制性的,每个省和地区都可以自由决定在这三个等级之后会发生什么。最后,为了表明已经取得了一些成绩,修院对礼仪、头衔和各省的新编号进行了详细的规定。[19]

Aftermath of Wilhelmsbad 威廉斯巴德的后果

What the Convent of Wilhelmsbad actually achieved was the demise of the Strict Observance. It renounced its own origin myth, along with the higher degrees which bound its highest and most influential members. It abolished the strict control which had kept the order united, and alienated many Germans who mistrusted Martinism. Bode, who was repelled by Martinism, immediately entered negotiations with Knigge, and finally joined the Illuminati in January 1783. Charles of Hesse joined the following month.[19]

威廉斯巴德修院实际上取得的成就是严格仪式的终结。它放弃了自己的起源神话,以及与其最高和最有影响力的成员联系在一起的高学位。它废除了维持秩序统一的严格控制,疏远了许多不信任马丁主义的德国人。被马丁教驱逐的波德立即与克尼格进行了谈判,并最终于1783年1月加入了光照派。黑森州的查尔斯于次月加入。[19]

Knigge's first efforts at an alliance with the intact German Grand Lodges failed, but Weishaupt persisted. He proposed a new federation where all of the German lodges would practise an agreed, unified system in the essential three degrees of Freemasonry, and be left to their own devices as to which, if any, system of higher degrees they wished to pursue. This would be a federation of Grand Lodges, and members would be free to visit any of the "blue" lodges, in any jurisdiction. All lodge masters would be elected, and no fees would be paid to any central authority whatsoever. Groups of lodges would be subject to a "Scottish Directorate", composed of members delegated by lodges, to audit finances, settle disputes, and authorise new lodges. These in turn would elect Provincial Directorates, who would elect inspectors, who would elect the national director. This system would correct the current imbalance in German Freemasonry, where masonic ideals of equality were preserved only in the lower three "symbolic" degrees. The various systems of higher degrees were dominated by the elite who could afford researches in alchemy and mysticism. To Weishaupt and Knigge, the proposed federation was also a vehicle to propagate Illuminism throughout German Freemasonry. Their intention was to use their new federation, with its emphasis on the fundamental degrees, to remove all allegiance to Strict Observance, allowing the "eclectic" system of the Illuminati to take its place.[19]

康尼格第一次尝试与完好无损的德国大 Lodges 结盟的努力失败了,但是维斯豪普特坚持下来了。他提议建立一个新的联邦,在这个联邦里,所有的德国居民都将在共济会的三个基本等级中实践一个统一的系统,如果有的话,他们可以自行决定追求哪一个更高等级的系统。这将是一个大分会联盟,成员可以自由参观任何管辖范围内的任何“蓝色”分会。所有小屋的主人都会被选举出来,而且不会向任何中央当局支付任何费用。分会集团将受“苏格兰理事会”的管辖,该理事会由分会委派的成员组成,负责审计财务状况,解决纠纷,并授权新的分会。这些机构依次选举省级管理局,省级管理局选举检查员,省级管理局选举国家管理局。这个系统将纠正德国共济会目前的不平衡,共济会的平等理想只保留在较低的三个“象征”等级。各种高学位的体系被精英们所支配,他们可以在炼金术和神秘主义方面进行研究。对于威斯豪普特和康尼格来说,这个联盟也是在整个德国共济会中宣传光明主义的工具。他们的意图是利用他们的新联邦,强调基本的程度,去除所有对严格遵守的忠诚,允许光照派的“折衷”系统取而代之。[19]

The circular announcing the new federation outlined the faults of German freemasonry, that unsuitable men with money were often admitted on the basis of their wealth, that the corruption of civil society had infected the lodges. Having advocated the deregulation of the higher grades of the German lodges, the Illuminati now announced their own, from their "unknown Superiors". Lodge Theodore, newly independent from Royal York, set themselves up as a provincial Grand Lodge. Knigge, in a letter to all the Royal York lodges, now accused that Grand Lodge of decadence. Their Freemasonry had allegedly been corrupted by the Jesuits. Strict Observance was now attacked as a creation of the Stuarts, devoid of all moral virtue. The Zinnendorf rite of the Grand Landlodge of the Freemasons of Germany was suspect because its author was in league with the Swedes. This direct attack had the opposite effect to that intended by Weishaupt, it offended many of its readers. The Grand Lodge of the Grand Orient of Warsaw, which controlled Freemasonry in Poland and Lithuania, was happy to participate in the federation only as far as the first three degrees. Their insistence on independence had kept them from the Strict Observance, and would now keep them from the Illuminati, whose plan to annex Freemasonry rested on their own higher degrees. By the end of January 1783 the Illuminati's masonic contingent had seven lodges.[19]

宣布成立新联邦的通知概述了德国共济会的缺陷,不适合有钱的人往往因为他们的财富而被承认,公民社会的腐败感染了会所。在主张放松对德国高级住所的管制之后,光照派现在宣布他们自己的,来自他们“未知的上级”。刚从皇家约克郡独立出来的洛奇 · 西奥多自立为一个省级大旅馆。克尼格在写给约克郡所有皇家客栈的信中,现在指责格兰德洛奇是个堕落的人。据说他们的共济会已经被耶稣会所腐化。严格遵守现在被攻击为斯图亚特的创造,缺乏所有的道德美德。德国共济会大兰德洛奇的辛内多夫仪式受到怀疑,因为它的作者与瑞典人是一伙的。这种直接的攻击与《魏思豪普特》的意图相反,它冒犯了许多读者。控制波兰和立陶宛共济会的华沙大东方主教堂,只是很高兴参加联邦的前三个等级。他们对独立的坚持使他们远离了严格的遵守,现在也使他们远离了光明会,光明会吞并共济会的计划建立在他们自己的更高级别上。到1783年1月底,光照派的共济会分会有了七个分会。[19]

It was not only the clumsy appeal of the Illuminati that left the federation short of members. Lodge Theodore was recently formed and did not command respect like the older lodges. Most of all, the Freemasons most likely to be attracted to the federation saw the Illuminati as an ally against the mystics and Martinists, but valued their own freedom too highly to be caught in another restrictive organisation. Even Ditfurth, the supposed representative of the Illuminati at Wilhelmsbad, had pursued his own agenda at the convent.[19]

这不仅仅是光照派笨拙的吸引力使得联盟缺少成员。洛奇 · 西奥多是最近才成立的,不像那些老房子那样受人尊敬。最重要的是,共济会最有可能被联盟所吸引,他们把光明会看作是反对神秘主义者和马丁主义者的盟友,但是他们对自己的自由评价太高,以至于不能被另一个限制性的组织所吸引。甚至连被认为是光照派在 Wilhelmsbad 的代表的迪特福斯,也在修道院里推行他自己的议程。[19]

The non-mystical Frankfurt lodges created an "Eclectic Alliance", which was almost indistinguishable in constitution and aims from the Illuminati's federation. Far from seeing this as a threat, after some discussion the Illuminati lodges joined the new alliance. Three Illuminati now sat on the committee charged with writing the new masonic statutes. Aside from strengthening relations between their three lodges, the Illuminati seem to have gained no advantage from this manoeuvre. Ditfurth, having found a masonic organisation that worked towards his own ambitions for Freemasonry, took little interest in the Illuminati after his adherence to the Eclectic Alliance. In reality, the creation of the Eclectic Alliance had undermined all of the subtle plans of the Illuminati to spread their own doctrine through Freemasonry.[19]

非神秘主义的法兰克福分会创建了一个“折衷主义联盟”,这在宪法和目标上与光照派的联盟几乎没有区别。经过一番讨论,光照派并没有将此视为威胁,而是加入了新的联盟。三个光照派现在坐在委员会负责编写新的共济会法规。除了加强他们三个分会之间的关系,光照派似乎没有从这一策略中获得任何优势。迪特福特建立了一个共济会组织,致力于实现他对共济会的抱负,在他加入折衷主义联盟之后,他对光照派并不感兴趣。事实上,折衷主义联盟的建立已经破坏了光明会通过共济会传播他们自己教义的所有微妙计划。[19]

Zenith

Although their hopes of mass recruitment through Freemasonry had been frustrated, the Illuminati continued to recruit well at an individual level. In Bavaria, the succession of Charles Theodore initially led to a liberalisation of attitudes and laws, but the clergy and courtiers, guarding their own power and privilege, persuaded the weak-willed monarch to reverse his reforms, and Bavaria's repression of liberal thought returned. This reversal led to a general resentment of the monarch and the church among the educated classes, which provided a perfect recruiting ground for the Illuminati. A number of Freemasons from Prudence lodge, disaffected by the Martinist rites of the Chevaliers Bienfaisants, joined lodge Theodore, who set themselves up in a gardened mansion which contained their library of liberal literature.[20]

尽管他们希望通过共济会进行大规模招募的愿望已经破灭,但是光明会继续在个人层面上招募人才。在巴伐利亚,查尔斯 · 西奥多(Charles Theodore)的继承最初导致了态度和法律的自由化,但是神职人员和朝臣们捍卫自己的权力和特权,劝说意志薄弱的君主逆转了他的改革,巴伐利亚对自由主义思想的压制又回来了。这种逆转导致了受教育阶层对君主和教会的普遍不满,这为光照派提供了一个完美的招募场所。一些来自普鲁登斯的共济会成员,对骑士比恩费桑特的马丁主义仪式不满,加入了西奥多的行列。[20]

Illuminati circles in the rest of Germany expanded. While some had only modest gains, the circle in Mainz almost doubled from 31 to 61 members. Reaction to state Catholicism led to gains in Austria, and footholds were obtained in Warsaw, Pressburg (Bratislava), Tyrol, Milan and Switzerland.[20]

德国其他地区的光照派圈子扩大了。尽管其中一些成员的收益不大,但在美因茨,这个圈子的成员数量几乎翻了一番,从31个增至61个。对国家天主教的反应导致在奥地利取得了进展,并在华沙,普雷斯堡(布拉迪斯拉发) ,Tyrol,米兰和瑞士获得了立足点。[20]

The total number of verifiable members at the end of 1784 is around 650. Weishaupt and Hertel later claimed a figure of 2,500. The higher figure is largely explained by the inclusion of members of masonic lodges that the Illuminati claimed to control, but it is likely that the names of all the Illuminati are not known, and the true figure lies somewhere between 650 and 2,500. The importance of the order lay in its successful recruitment of the professional classes, churchmen, academics, doctors and lawyers, and its more recent acquisition of powerful benefactors. Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg with his brother and later successor August, Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg governor of Erfurt, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (already mentioned), his chief assistant in masonic matters, Johann Friedrich von Schwarz, and Count Metternich of Koblenz were all enrolled. In Vienna, Count Brigido, governor of Galicia, Count Leopold Kolowrat, chancellor of Bohemia with his vice-Chancellor Baron Kressel, Count Pálffy von Erdöd, chancellor of Hungary, Count Banffy, governor and provincial Grand Master of Transylvania, Count Stadion, ambassador to London, and Baron von Swieten, minister of public education, also joined.[20]

到1784年底,可核实成员的总数约为650人。威斯豪普特和赫特尔后来声称这一数字为2500。较高的数字主要是由于包含了共济会的成员,光明会声称控制,但它很可能是所有的光明会的名称不知道,真正的数字在650到2500之间。这个组织的重要性在于它成功地招募了专业阶层---- 教士、学者、医生和律师---- 以及它最近招募了一些有权势的捐助者。卡尔 · 奥古斯特,萨克森-魏玛-艾森纳赫大公,欧内斯特二世,萨克森-哥达-阿尔滕堡公爵和他的兄弟,后来的继任者奥古斯特,卡尔 · 西奥多 · 安东 · 玛利亚 · 达尔伯格,爱尔福特州长,斐迪南 · 德尔伯格,他的共济会事务首席助理,约翰 · 弗里德里希 · 冯 · 施瓦茨,以及科布伦茨的麦特涅伯爵都入学了。在维也纳,加利西亚州长布里吉多伯爵、波希米亚总理利奥波德•科洛拉特伯爵(Count Brigido)及其副总理拜伦•克雷塞尔(Baron Kressel)、匈牙利总理帕尔菲•冯•埃尔德德伯爵(Count Pálffy von Erdöd)、特兰西瓦尼亚州州长兼省长班菲伯爵(Count Banffy)、驻伦敦大使斯塔迪翁伯爵(Count Stadion) ,以及公共教育部长巴伦•冯•斯。[20]

There were notable failures. Johann Kaspar Lavater, the Swiss poet and theologian, rebuffed Knigge. He did not believe the order's humanitarian and rationalist aims were achievable by secret means. He further believed that a society's drive for members would ultimately submerge its founding ideals. Christoph Friedrich Nicolai, the Berlin writer and bookseller, became disillusioned after joining. He found its aims chimeric, and thought that the use of Jesuit methods to achieve their aims was dangerous. He remained in the order, but took no part in recruitment.[20]

有一些明显的失败。瑞士诗人和神学家约翰 · 卡斯帕 · 拉瓦特断然拒绝了康吉。他不相信该命令的人道主义和理性主义目标是可以通过秘密手段实现的。他进一步认为,一个社会对成员的吸引力最终会淹没其创始理想。柏林作家、书商克里斯托弗•弗里德里希•尼古拉(Christoph Friedrich Nicolai)加入该组织后,对该组织的幻想破灭了。他发现其目的是不切实际的,并认为使用耶稣会士的方法来达到他们的目的是危险的。他继续留任,但没有参加招募工作。[20]

Conflict with Rosicrucians 与玫瑰十字会的冲突

At all costs, Weishaupt wished to keep the existence of the order secret from the Rosicrucians, who already had a considerable foothold in German Freemasonry. While clearly Protestant, the Rosicrucians were anything but anticlerical, were pro-monarchic, and held views clearly conflicting with the Illuminati vision of a rationalist state run by philosophers and scientists. The Rosicrucians were not above promoting their own brand of mysticism with fraudulent seances. A conflict became inevitable as the existence of the Illuminati became more evident, and as prominent Rosicrucians, and mystics with Rosicrucian sympathies, were actively recruited by Knigge and other over-enthusiastic helpers. Kolowrat was already a high ranking Rosicrucian, and the mystic Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel had a very low opinion of the rationalist higher grades of the Illuminati.[20]

不惜一切代价,卫斯豪普特希望对已经在德国共济会中占有一席之地的蔷薇十字会成员保密。虽然显然是新教徒,蔷薇十字会绝不是反教会的,而是亲君主制的,他们的观点明显与光明会的理性主义观点相冲突,光明会的观点是由哲学家和科学家管理的。蔷薇十字会的成员们并不介意用欺骗性的降神会来宣扬他们自己的神秘主义品牌。随着光明会的存在变得越来越明显,一场冲突变得不可避免,杰出的蔷薇十字会成员,以及拥有蔷薇十字会同情心的神秘主义者,被 Knigge 和其他热情过度的帮助者积极招募。科洛拉特已经是蔷薇十字会的高级成员,而神秘的查尔斯伯爵(黑森-卡塞尔)对理性主义者在光明会的高等级评价非常低。[20]

The Prussian Rosicrucians, under Johann Christoph von Wöllner, began a sustained attack on the Illuminati. Wöllner had a specially engineered room in which he convinced potential patrons of the effectiveness of Rosicrucian "magic", and his order had acquired effective control of the "Three Globes" and its attached lodges. Through this mouthpiece, the Illuminati were accused of atheism and revolutionary tendencies. In April 1783, Frederick the Great informed Charles of Hesse that the Berlin lodges had documents belonging to the Minervals or Illuminati which contained appalling material, and asked if he had heard of them. All Berlin masons were now warned against the order, which was now accused of Socinianism, and of using the liberal writings of Voltaire and others, alongside the tolerance of Freemasonry, to undermine all religion. In November 1783, the Three Globes described the Illuminati as a masonic sect which sought to undermine Christianity and turn Freemasonry into a political system. Their final anathema, in November 1784, refused to recognise any Illuminati as Freemasons.[20]

普鲁士的蔷薇十字会,在约翰 · 克里斯托弗 · 冯 · 沃尔纳的领导下,开始了对光照派的持续攻击。沃尔纳有一间经过特别设计的房间,他在里面使潜在的顾客相信蔷薇十字会的“魔法”是有效的,他的命令获得了对“三个金球奖”及其附属会所的有效控制。通过这个喉舌,光明会被指责为无神论者和革命倾向。1783年4月,腓特烈二世通知黑森的查尔斯,柏林的小屋有属于矿物会或光明会的文件,其中包含骇人听闻的材料,并询问他是否听说过他们。所有柏林的共济会员现在都受到警告,反对这个现在被指责为社会主义的组织,反对使用伏尔泰和其他人的自由主义著作,以及对共济会的宽容,来破坏所有的宗教。1783年11月,三个金球奖将光明会描述为一个共济会教派,它试图破坏基督教,并将共济会变成一个政治体系。1784年11月,他们的最后一次诅咒,拒绝承认任何光明会成为共济会。[20]

In Austria, the Illuminati were blamed for anti-religious pamphlets that had recently appeared. The Rosicrucians spied on Joseph von Sonnenfels and other suspected Illuminati, and their campaign of denunciation within Freemasonry completely shut down Illuminati recruitment in Tyrol.[20]

在奥地利,光照派因最近出版的反宗教小册子而受到指责。玫瑰十字会暗中监视 Joseph von Sonnenfels 和其他被怀疑是光明会成员的人,他们在共济会内部发起的谴责运动完全阻止了光明会在 Tyrol 的招募活动。[20]

The Bavarian Illuminati, whose existence was already known to the Rosicrucians from an informant, were further betrayed by the reckless actions of Ferdinand Maria Baader, an Areopagite who now joined the Rosicrucians. Shortly after his admission it was made known to his superiors that he was one of the Illuminati, and he was informed that he could not be a member of both organisations. His letter of resignation stated that the Rosicrucians did not possess secret knowledge, and ignored the truly Illuminated, specifically identifying Lodge Theodore as an Illuminati Lodge.[20]

光照派的存在已经被蔷薇十字会的告密者所知,但是他的鲁莽行为进一步背叛了他,他是一个阿鲁巴人,现在加入了蔷薇十字会。在他承认之后不久,他的上级就知道他是光明会的成员,他被告知他不能同时是这两个组织的成员。他的辞职信称蔷薇十字会并不拥有秘密知识,并且无视真正被照亮的人,特别指出洛奇 · 西奥多是光明会的成员。[20]

Internal dissent 内部异议

As the Illuminati embraced Freemasonry and expanded outside Bavaria, the council of the Areopagites was replaced by an ineffective "Council of Provincials". The Areopagites, however, remained as powerful voices within the Order, and began again to bicker with Weishaupt as soon as Knigge left Munich. Weishaupt responded by privately slandering his perceived enemies in letters to his perceived friends.[20]

当光明会拥抱共济会并在巴伐利亚以外扩张时,阿鲁帕吉特派的理事会被一个无效的“省会理事会”所取代。然而,在奥匈帝国内部,奥匈帝国的支持者们仍然保持着强有力的声音,一旦康尼格离开慕尼黑,他们就开始和威斯豪普特争吵起来。威斯豪普特的回应是私下里给他的知己朋友写信诽谤他的知己。[20]

More seriously, Weishaupt succeeded in alienating Knigge. Weishaupt had ceded considerable power to Knigge in deputising him to write the ritual, power he now sought to regain. Knigge had elevated the Order from a tiny anti-clerical club to a large organisation, and felt that his work was under-acknowledged. Weishaupt's continuing anti-clericalism clashed with Knigge's mysticism, and recruitment of mystically inclined Freemasons was a cause of friction with Weishaupt and other senior Illuminati, such as Ditfurth. Matters came to a head over the grade of Priest. The consensus among many of the Illuminati was that the ritual was florid and ill-conceived, and the regalia puerile and expensive. Some refused to use it, others edited it. Weishaupt demanded that Knigge rewrite the ritual. Knigge pointed out that it was already circulated, with Weishaupt's blessing, as ancient. This fell on deaf ears. Weishaupt now claimed to other Illuminati that the Priest ritual was flawed because Knigge had invented it. Offended, Knigge now threatened to tell the world how much of the Illuminati ritual he had made up. Knigge's attempt to create a convention of the Areopagites proved fruitless, as most of them trusted him even less than they trusted Weishaupt. In July 1784 Knigge left the order by agreement, under which he returned all relevant papers, and Weishaupt published a retraction of all slanders against him.[20] In forcing Knigge out, Weishaupt deprived the order of its best theoretician, recruiter, and apologist.[18]

更严重的是,威斯豪普特成功地疏远了康尼格。威斯豪普特已经把相当大的权力让给了康尼格,让他代写这个仪式,他现在正在寻求重新获得这个权力。克尼格已经把教会从一个小小的反教会俱乐部提升为一个大组织,他觉得自己的工作没有得到足够的认可。维斯豪普特持续的反教权主义与康尼格的神秘主义发生了冲突,招募有神秘倾向的共济会成员是导致维斯豪普特与其他高级光明会成员,如迪特福的摩擦的原因。事情的严重性超过了牧师的级别。许多光照派的共识是,这个仪式是华丽的和考虑不周的,以及幼稚和昂贵的盛宴。一些人拒绝使用它,其他人编辑它。威斯豪普特要求康尼吉改写仪式。康尼基指出,这本书在威斯豪普特的祝福下,已经像古代一样流传开来了。对此置若罔闻。维斯豪普特现在向其他光照派宣称牧师仪式是有缺陷的,因为是康尼基发明了它。受到了冒犯,克尼格现在威胁要告诉全世界他编造了多少光照派的仪式。康尼基试图创建一个亚略巴基派的传统,但是没有成功,因为他们中的大多数人对他的信任甚至比对威斯豪普特的信任还要少。1784年7月,康尼格签订协议,退回所有相关文件,并发表了一份收回所有诽谤他的文章的声明。[20]在强迫康尼基离开的过程中,威斯豪普特剥夺了它最好的理论家、招募者和辩护者的秩序。[18]

Decline 衰退

The final decline of the Illuminati was brought about by the indiscretions of their own Minervals in Bavaria, and especially in Munich. In spite of efforts by their superiors to curb loose talk, politically dangerous boasts of power and criticism of monarchy caused the "secret" order's existence to become common knowledge, along with the names of many important members. The presence of Illuminati in positions of power now led to some public disquiet. There were Illuminati in many civic and state governing bodies. In spite of their small number, there were claims that success in a legal dispute depended on the litigant's standing with the order. The Illuminati were blamed for several anti-religious publications then appearing in Bavaria. Much of this criticism sprang from vindictiveness and jealousy, but it is clear that many Illuminati court officials gave preferential treatment to their brethren. In Bavaria, the energy of their two members of the Ecclesiastical Council had one of them elected treasurer. Their opposition to Jesuits resulted in the banned order losing key academic and church positions. In Ingolstadt, the Jesuit heads of department were replaced by Illuminati.[21]

光照派最终的衰落是由于他们自己在巴伐利亚,尤其是在慕尼黑的矿区的轻率行为所导致的。尽管他们的上级努力制止放荡的言论,但政治上危险的权力吹嘘和对君主制的批评使“秘密”秩序的存在成为众所周知的事实,连同许多重要成员的名字。光照派在权力的位置上的存在现在导致了一些公众的不安。在许多公民和国家管理机构中都有光明会成员。尽管人数不多,但有人声称,法律纠纷的胜诉取决于诉讼当事人对命令的支持程度。光明会被指责为几个反宗教的出版物,然后出现在巴伐利亚。这些批评大多源于报复和嫉妒,但很明显,许多光照派法庭官员对他们的同胞给予了优待。在巴伐利亚,他们两个教会理事会成员的精力都集中在其中一个选举出来的财政部长身上。他们对耶稣会的反对导致了被禁止的命令失去了关键的学术和教会职位。在因戈尔施塔特,耶稣会的部门主管被光明会取代。[21]

Alarmed, Charles Theodore and his government banned all secret societies including the Illuminati.[22] A government edict dated 2 March 1785 "seems to have been deathblow to the Illuminati in Bavaria". Weishaupt had fled and documents and internal correspondence, seized in 1786 and 1787, were subsequently published by the government in 1787.[23] Von Zwack's home was searched and much of the group's literature was disclosed.[4]

警觉之下,查尔斯 · 西奥多和他的政府禁止了包括光照派在内的所有秘密组织。[22]1785年3月2日的一项政府法令“似乎是对巴伐利亚的光照派的致命打击”。1786年和1787年被没收的文件和内部通信,随后在1787年由政府公布。[23]冯 · 兹瓦克的家被搜查,该组织的大部分文献被披露。[4]

Barruel and Robison 巴鲁埃尔和罗宾逊

Between 1797 and 1798, Augustin Barruel's Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism and John Robison's Proofs of a Conspiracy publicised the theory that the Illuminati had survived and represented an ongoing international conspiracy. This included the claim that it was behind the French Revolution. Both books proved to be very popular, spurring reprints and paraphrases by others.[24] A prime example of this is Proofs of the Real Existence, and Dangerous Tendency, Of Illuminism by Reverend Seth Payson, published in 1802.[25] Some of the response to this was critical, for example Jean-Joseph Mounier's On the Influence Attributed to Philosophers, Free-Masons, and to the Illuminati on the Revolution of France.[26][27]

在1797年至1798年间,奥古斯丁 · 巴鲁尔的《阐释雅各宾派历史的回忆录》和约翰 · 罗宾逊的《阴谋论证》宣传了光照派幸存下来并代表了一个持续的国际阴谋的理论。这包括声称它是法国大革命的幕后主使。事实证明,这两本书都非常受欢迎,促使他人重印和改写。[24]这方面的一个主要例子是塞思 · 佩森牧师于1802年出版的《光明主义的真实存在的证据和危险的倾向》。[25]对此的一些反应是批判性的,例如让-约瑟夫 · 莫尼埃的《论哲学家、自由共济会和光明会对法国大革命的影响》。[26]

The works of Robison and Barruel made their way to the United States and across New England. The Rev. Jedidiah Morse, an orthodox Congregational minister and geographer, was among those who delivered sermons against the Illuminati. In fact, one of the first accounts of the Illuminati to be printed in the United States was Morse's Fast Day sermon of 9 May 1798. Morse had been alerted to the publication in Europe of Robison's Proofs of a Conspiracy by a letter from the Rev. John Erskine of Edinburgh, and he read Proofs shortly after copies published in Europe arrived by ship in March of that year. Other anti-Illuminati writers, such as Timothy Dwight, soon followed in their condemnation of the imagined group of conspirators.[28]

罗宾逊和巴鲁埃尔的作品流传到了美国并穿越了新英格兰。牧师杰迪戴亚 · 莫尔斯是一位正统公理会的牧师和地理学家,也是发表反对光照派的布道的人之一。事实上,光照派最早在美国印刷的记录之一就是莫尔斯1798年5月9日的斋日布道。爱丁堡的约翰 · 厄斯金牧师的一封信提醒莫尔斯在欧洲出版罗宾逊的《阴谋论证明》 ,他在那年3月份《证明》在欧洲出版后不久就读了这本书。其他反光照派的作家,比如提摩西 · 德怀特,很快也开始谴责想象中的阴谋家。[28]

Printed sermons were followed by newspaper accounts, and these figured in the partisan political discourse leading up to the 1800 U.S. presidential election.[29] The subsequent panic also contributed to the development of gothic literature in the United States. At least two novels from the period make reference to the crisis: Ormond; or, The Secret Witness (1799) and Julia, and the Illuminated Baron (1800).[30] Some scholars, moreover, have linked the panic over the alleged Illuminati conspiracy to fears about immigration from the Caribbean and about potential slave rebellions.[28] Concern died down in the first decade of the 1800s, although it revived from time to time in the Anti-Masonic movement of the 1820s and 30s.[6]

布道文章印刷出来后,报纸纷纷登载,这些文字在1800年美国总统大选之前的党派政治话语中占有重要地位。[29]随后的恐慌也促进了美国哥特小说的发展。这一时期至少有两部小说提到了这场危机: 《奥蒙德》(Ormond)、《秘密证人》(1799)和《朱莉娅》(Julia) ,以及《被照亮的男爵》(The Illuminated Baron)(1800)。[30]此外,一些学者把所谓的光明会阴谋引起的恐慌与对来自加勒比海地区的移民和潜在的奴隶起义的恐惧联系起来。关注在19世纪头十年逐渐消失,尽管在19世纪20年代和30年代的 Anti-Masonic Party(英文)时期它又不时地复苏。[6]

Modern Illuminati 现代光照派

Several recent and present-day fraternal organisations claim to be descended from the original Bavarian Illuminati and openly use the name "Illuminati". Some of these groups use a variation on the name "The Illuminati Order" in the name of their own organisations,[31] while others, such as the Ordo Templi Orientis, have "Illuminati" as a grade within their organisation's hierarchy. However, there is no evidence that these present-day groups have any real connection to the historic order. They have not amassed significant political power or influence, and most, rather than trying to remain secret, promote unsubstantiated links to the Bavarian Illuminati as a means of attracting membership.[22]

一些最近的和现在的兄弟组织声称是最初的光照派的后裔,并公开使用“光照派”的名称。其中一些组织以自己组织的名义使用“光明会秩序”这个名称的变体,而另一些组织,比如东方圣殿会,在他们组织的等级体系中将“光明会”作为一个等级。然而,没有证据表明这些当今的团体与历史秩序有任何真正的联系。他们并没有积累大量的政治权力或影响力,大多数人并没有试图保持秘密,而是宣传与光照派的未经证实的联系,以此作为吸引成员的一种手段。[22]

Legacy 遗产

The Illuminati did not survive their suppression in Bavaria. Their further mischief and plottings in the work of Barruel and Robison must be thus considered as the invention of the writers.[6] Despite this, they have been featured in many modern conspiracy theories predicated on their survival.

光照派在巴伐利亚没有幸免于他们的镇压。因此,他们在 Barruel 和罗宾逊作品中的进一步恶作剧和陷阱必须被认为是作家们的创造。[6]尽管如此,许多现代阴谋论都以他们的生存为依据,描述了他们的特征。

Conspiracy theorists and writers such as Mark Dice have argued that the Illuminati have survived to this day.[32]

阴谋论者和作家,如马克 · 戴斯,认为光照派至今仍然存在

Many conspiracy theories propose that world events are being controlled and manipulated by a secret society calling itself the Illuminati.[33] Conspiracy theorists have claimed that many notable people were or are members of the Illuminati. Presidents of the United States are a common target for such claims.[34][35]

许多阴谋论认为,世界事件正在被一个自称为光照派的秘密社团控制和操纵。[33]阴谋论者声称许多著名人士曾经是或现在是光照派的成员。美国总统是这种要求的共同目标。[34][35]

Other theorists contend that a variety of historical events were orchestrated by the Illuminati, from the French Revolution, the Battle of Waterloo and the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, to an alleged communist plot to hasten the "New World Order" by infiltrating the Hollywood film industry.[36][37]

其他理论家认为,从法国大革命、滑铁卢战役和暗杀美国总统约翰肯尼迪,到所谓的共产主义阴谋通过渗透到好莱坞电影业来加速“新世界秩序”,一系列的历史事件都是由光明会精心策划的。[37]

References 参考资料

- ^ /ɪˌluːmɪˈnɑːti鲁曼提/

- ^ Richard van Dülmen, The Society of Enlightenment (Polity Press 1992) p. 110

- 理查德 · 范 · 杜尔曼,《启蒙社会》(政治出版社,1992) ,第110页

- ^ René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, pp. 453, 468–469, 507–508, 614–615

- 1914,pp. 453,468-469,507-508,614-615

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b Introvigne, Massimo (2005). "Angels & Demons from the Book to the Movie FAQ – Do the Illuminati Really Exist?". Center for Studies on New Religions. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Schüttler, Hermann (1991). Die Mitglieder des Illuminatenordens, 1776–1787/93. Munich: Ars Una. pp. 48–49, 62–63, 71, 82. ISBN 978-3-89391-018-2.

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b c d Vernon Stauffer, New England and the Bavarian Illuminati, Columbia University Press, 1918, Chapter 3 The European Illuminati, Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon, accessed 14 November 20151918,Chapter 3 The European Illuminati,Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon,accessed 14 November 2015. 新英格兰和光照派,哥伦比亚大学出版社,1918,Chapter 3 The European Illuminati,Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon

- ^ Weishaupt, Adam (1790). Pythagoras oder Betrachtungen über die geheime Welt- und Regierungskunst. Frankfurt and Leipzig: Frankfurt ; Leipzig. p. 670.

- ^ René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 1, Chapter 1, pp. 15–29

- 弗雷斯蒂埃回忆录,《巴维耶尔与法郎-马科纳里的通行证》 ,巴黎,1914年,第1卷,第1章,第15-29页

- ^ Manfred Agethen, Geheimbund und Utopie. Illuminaten, Freimaurer und deutsche Spätaufklärung, Oldenbourg, Munich, 1987, p. 150.

- 1987年,《光照、自由和德国社会责任》 ,Oldenbourg,慕尼黑,第150页。

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b c René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 1, Chapter 2, pp. 30–45勒内 · 勒弗雷斯蒂埃,《巴维耶尔与法郎-马科纳里的通行证》 ,巴黎,1914年,第一卷,第二章,第30-45页

- ^ Terry Melanson, Perfectibilists: The 18th Century Bavarian Order of the Illuminati, Trine Day, 2009, pp. 361, 364, 428

- 特里 · 梅兰森,《完美主义者: 18世纪巴伐利亚光照派秩序》 ,三日,2009,第361,364,428页

- ^ Ed Josef Wäges and Reinhard Markner, tr Jeva Singh-Anand, The Secret School of Wisdom, Lewis Masonic 2015, pp. 15–16

- 埃德•约瑟夫•韦格斯(Ed Josef Wäges)和莱茵哈德•马克纳(Reinhard Markner) ,tr Jeva Singh-Anand,The Secret School of Wisdom,Lewis Masonic 2015,pp. 15-16

- ^ Ellic Howe, Illuminati, Man, Myth and Magic (partwork), Purnell, 1970, vol 4, pp. 1402–04

- ^ Ellic Howe,Illuminati,Man,Myth and Magic (部分作品) ,Purnell,1970,vol 4,pp. 1402-04

- ^ René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 1, Chapter 3, pp. 45–72.

- 弗雷斯蒂埃回忆录,《巴维耶尔与法郎-马科纳里的单身生活》 ,巴黎,1914年,第1卷,第3章,第45-72页。

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b c René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 3 Chapter 1, pp. 193–201勒内 · 勒弗雷斯蒂埃,《光明的巴维埃和法郎-马科纳里的通行证》 ,巴黎,1914年,第3卷第1章,第193-201页

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 3 Chapter 2, pp. 202–26勒内 · 勒弗雷斯蒂埃,《光明的巴维埃和法郎-马科纳里的通行证》 ,巴黎,1914年,第3卷,第2章,第202-26页

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b c d e f g René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 3 Chapter 3, pp. 227–50勒内 · 勒弗雷斯蒂埃,《光明的巴维埃和法郎-马科纳里的通行证》 ,巴黎,1914年,第3卷第3章,第227-50页

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b K. M. Hataley, In Search of the Illuminati, Journal of the Western Mystery Tradition, No. 23, Vol. 3. Autumnal Equinox 2012哈塔利,《寻找光照派》 ,《西方神秘传统杂志》 ,第23卷,第3卷。九月分点2012年

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b c d e f g h i j k l René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 4 Chapter 1, pp. 343–88勒内 · 勒弗雷斯蒂埃,《光明的巴维埃和法郎-马科纳里的通行证》 ,巴黎,1914年,第4卷第1章,第343-88页

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b c d e f g h i j René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 4 Chapter 2, pp. 389–429勒内 · 勒弗雷斯蒂埃,《光明的巴维埃和法郎-马科纳里的快板》 ,巴黎,1914年,第4卷第2章,第389-429页

- ^ René le Forestier, Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande, Paris, 1914, Book 4 Chapter 3, pp. 430–96

- 《森林》 ,《巴维耶尔和法郎-马克纳里的光明》 ,巴黎,1914年,第4卷,第3章,第430-96页

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b McKeown, Trevor W. (16 February 2009). "A Bavarian Illuminati Primer". Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon A.F. & A.M. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Roberts, J.M. (1974). The Mythology of Secret Societies. NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 128–29. ISBN 978-0-684-12904-4.

- ^ Simpson, David (1993). Romanticism, Nationalism, and the Revolt Against Theory. University of Chicago Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-226-75945-6..

- ^ Payson, Seth (1802). Proofs of the Real Existence, and Dangerous Tendency, Of Illuminism. Charlestown: Samuel Etheridge. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Tise, Larry (1998). The American Counterrevolution: A Retreat from Liberty, 1783–1800. Stackpole Books. pp. 351–53. ISBN 978-0-8117-0100-6.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (17 November 1802). "'There has been a book written lately by DuMousnier ...'" (PDF). Letter to Nicolas Gouin Dufief. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: 跳到:a b Fraser, Gordon (November 2018). "Conspiracy, Pornography, Democracy: The Recurrent Aesthetics of the American Illuminati". Journal of American Studies. 54 (2): 273–294. doi:10.1017/S0021875818001408. S2CID 150279924 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Stauffer, Vernon (1918). "New England and the Bavarian Illuminati." PhD diss., Columbia Univ., pp. 282–283, 304–305, 307, 317, 321, 345–360. Retrieved July 14, 2019

- ^ 斯托弗,弗农(1918)。新英格兰和光照派282-283,304-305,307,317,321,345-360.14,2019

- ^ Wood, Sally Sayward Barrell Keating (1800). Julia, and the illuminated baron: a novel: founded on recent facts, which have transpired in the course of the late revolution of moral principles in France. Portsmouth, New-Hampshire: Printed at the United States' Oracle Press, by Charles Peirce, (proprietor of the work.). OCLC 55824226.

- ^ Weishaupt, Adam. The Illuminati Series. Hyperreality Books, 2011. 6 vols.

- 《光照派》 ,《超现实图书》 ,2011.6卷。

- ^ Sykes, Leslie (17 May 2009). "Angels & Demons Causing Serious Controversy". KFSN-TV/ABC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Barkun, Michael (2003). A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Comparative Studies in Religion and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23805-3.

- ^ Howard, Robert (28 September 2001). "United States Presidents and The Illuminati / Masonic Power Structure". Hard Truth/Wake Up America. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ "The Barack Obama Illuminati Connection". The Best of Rush Limbaugh Featured Sites. 1 August 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Mark Dice 马克 · 戴斯, The Illuminati: Facts & Fiction 光照派: 事实与虚构, 2009. 2009年ISBN 国际标准书号 0-9673466-5-7

- ^ Myron Fagan, The Council on Foreign Relations. Council On Foreign Relations By Myron Fagan Archived 9 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- 迈伦 · 费根,外交关系委员会。对外关系委员会作者: Myron Fagan 2014年7月9日在 Wayback Machine

Further reading 进一步阅读

- Engel, Leopold (1906). Geschichte des Illuminaten-ordens (in German). Berlin: Hugo Bermühler verlag. OCLC 560422365. (Wikisource) (维基资源)

- Gordon, Alexander (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 320.

- Hermann Schüttler, Reinhard Markner, Forschungsliteratur zum Illuminatenorden / Research Bibliography at Illuminaten Wiki

- Hermann Schüttler,Reinhard Markner,Forschungsliteratur zum Illuminatenorden/Research 书目在 Illuminaten Wiki

- Johnson, George (1983). Architects of Fear. ISBN 9780874772753.

- Le Forestier, René (1914). Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie. OCLC 493941226.

- Markner, Reinhold; Neugebauer-Wölk, Monika; Schüttler, Hermann, eds. (2005). Die Korrespondenz des Illuminatenordens. Bd. 1, 1776–81 (in German). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. ISBN 978-3-484-10881-3.

- Melanson, Terry (2009). Perfectibilists: The 18th Century Bavarian Order of the Illuminati. Walterville, OR: Trine Day. ISBN 978-0-9777953-8-3. OCLC 182733051.

- Mounier, Jean-Joseph (1801). On the Influence Attributed to Philosophers, Free-Masons, and to the Illuminati on the Revolution of France. Trans. J. Walker. London: W. and C. Spilsbury. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Livingstone, David (2011). Terrorism and the Illuminati: A Three-thousand-year History. Progressive Press. ISBN 978-1-61577-306-0. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Porter, Lindsay (2005). Who Are the Illuminati?: Exploring the Myth of the Secret Society. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-84340-289-3. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Robison, John (1798). Proofs of a Conspiracy Against All the Religions and Governments of Europe, Carried on in the Secret Meetings of Free Masons, Illuminati, and Reading Societies (3 ed.). London: T. Cadell, Jr. and W. Davies. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Utt, Walter C. (1979). "Illuminating the Illuminati" (PDF). Liberty. 74 (3, May–June): 16–19, 26–28. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- Burns, James; Utt, Walter C. (1980). "Further Illumination: Burns Challenges Utt and Utt Responds" (PDF). Liberty. 75 (2, March–April): 21–23. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

External links 外部链接

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illuminati.维基共享资源有与光明会相关的媒体。 |

- Gordon, Alexander (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 320.

- Gruber, Hermann (1910). "Illuminati". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. NY: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 661–63. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Melanson, Terry (5 August 2005). "Illuminati Conspiracy Part One: A Precise Exegesis on the Available Evidence". Conspiracy Archive. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- Illuminati 光照派

- 1776 establishments in the Holy Roman Empire在神圣罗马帝国的1776个机构

- 1785 disestablishments in the Holy Roman Empire1785年神圣罗马帝国的废墟

- 18th-century establishments in Bavaria 18世纪在巴伐利亚的建筑

- 18th-century disestablishments in Bavaria 18世纪巴伐利亚的废墟

- Conspiracy theories 阴谋论

- Organisations based in Bavaria 总部设在巴伐利亚的组织

- Organizations disestablished in 1785 组织于1785年解散

- Organizations established in 1776 1776年成立的组织

- Secret societies in Germany 德国的秘密社团

- Secularism in Germany 德国的世俗主义

- Freemasonry-related controversies 共济会相关的争论